A recently published study from University College London (UCL) has shown that roads in the capital without dedicated cycling infrastructure saw the most near-miss cycling incidents.

The study involved 60 London-based cyclists who recorded their commutes on a 360-degree helmet camera over a two-week period. It is thought to be the first to combine video footage, GPS data and verbal reporting to allow researchers to understand the various factors that contribute to near-miss incidents between cyclists and other road users.

From the 317 hours of footage gathered, 94 near-miss events were recorded, although there were no actual collisions during the study period.

Researchers found that the near misses were most likely to occur during peak commuting hours (7am – 9.59am and 5pm – 7.59pm) and on roads that lacked dedicated cycling infrastructure.

In total, 58 out of 94 near misses occurred during peak hours, while 69 occurred on roads without cycling infrastructure.

The study also showed that higher cycling speeds and greater use of cycleways away from main roads were associated with fewer near misses.

Professor Nicola Christie, senior author of the study from UCL Centre for Transport Studies, said: ‘Cycling near misses are often overlooked in official statistics, yet they are crucial indicators of road safety. Our findings show that most near misses happen on roads without cycling infrastructure, and that junctions are particularly hazardous.'

Cycling activity rose by 39% in Great Britain over the 20 years between 2004 and 2024, and, whilst the number of cyclists killed on roads fell by 35% during this period to 82 deaths in 2024, there was an increase in the number of serious injuries by 16%, with 3,822 incidents in 2024.

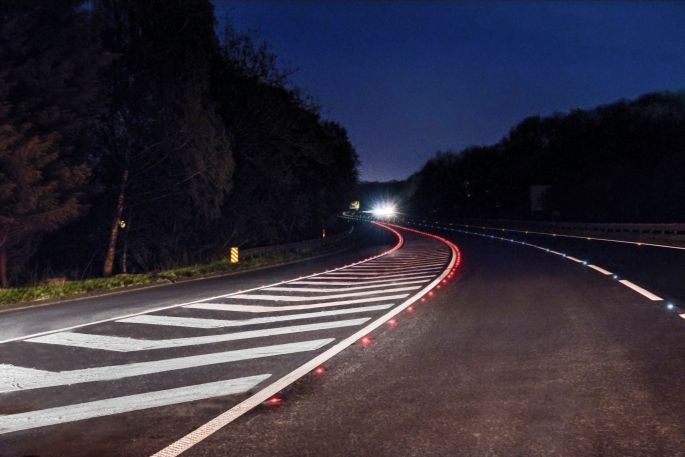

Dr James Haworth, an author of the study from SpaceTimeLab, based in UCL Civil, Environmental and Geomatic Engineering, said: ‘In general, our findings support the idea that creating dedicated cycling infrastructure and well-planned cycle routes has a positive impact on road safety. Cycleways navigating through quieter residential streets – formerly called ‘quietways' – were associated with fewer near misses, despite the fact the rider shares the lane with motor vehicles.

‘That being said, we did observe near misses on segregated cycle ways – formerly called cycle superhighways in London – where riders and vehicles come into conflict. This was evident where vehicles have to pull out from side roads across the cycle way, for example, or have to turn across oncoming traffic into a side road, particularly in congested periods where visibility is limited.

‘So I would say that there is some evidence that using quiet, residential streets for cycle ways is working as a policy because it keeps bicycle traffic away from car traffic.'

Ruth Purdie OBE, chief executive at The Road Safety Trust, which funded the study, said: ‘It's important that we fully understand the incidents and near misses that cyclists experience if we are to make improvements to road infrastructure that support safe cycling'

The full study is available to read here.