The former director at the Department for Transport and current RAC Foundation director discusses when and how we should hang up the keys.

Most regular readers of Highways magazine will have set up automatic alerts so they are among the first to read new reports published by the RAC Foundation. By now, you will have read Dr Julie Gandolfi's extensive study, looking at approaches being taken around the world to keep older drivers driving safely. But if you haven't, may I commend it to you?

To put some numbers on the table, there are already 5.5 million driving licence holders in Britain aged 70 or over. That's 41% more than the 3.9 million licence holders in the same age group back in 2012. And this is, largely, a generation of people whose lifestyles have been heavily shaped by their ability to own and drive a car – a vehicle that offers a degree of comfort and convenience that even a minicab struggles to match.

It's not only that the number of older people is rising as a proportion of the total population, but they are living longer, too. The good news is that many older drivers self-regulate their driving – avoiding busy roads at busy times; not driving at night or in poor weather conditions.

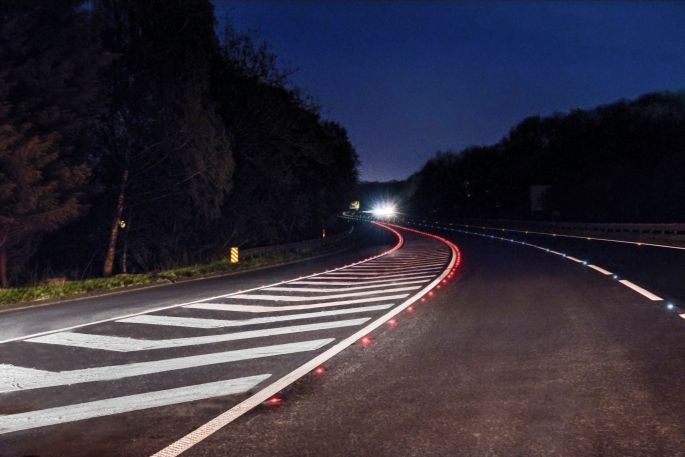

But while many people are staying fit and active well into retirement there are some aspects of ageing that catch up with us all eventually – our eyesight deteriorates, our cognitive ability reduces, and we become frailer and liable to injury. Evidence from America suggests that the amount of light needed by a 72-year-old to drive safely is an astonishing 16 times than that required by a 20-year-old.

This explains why alongside ‘Rail fare shock' and ‘Phew, what a scorcher', we routinely read calls in the media for compulsory re-testing of drivers over a certain age.

There are three very clear problems with this call. First, at what age?

We all grow older at the same pace, but the same cannot be said for the decline in our physical and mental abilities – my physique may be the envy of a younger man, but he wouldn't want my eyesight. Second, we don't want to deter those safe older drivers who do self-regulate and thus are better able to stay active, mobile and connected.

Third, even if we did decide that we should have a test and could decide at what age we'd take it, we'd then have to decide what form it should take, which turns out to be a far greater challenge than you might have thought.

The phenomenon of an ageing population isn't unique to the UK – it is probably at its most pronounced in Japan. Dr Gandolfi's report reveals how hard it has proved to devise a test for older drivers that demonstrably reduces road safety risk, even for the extreme set of hurdles facing older Japanese drivers, who, after the age of 70, must take part in a lecture, a battery of driver aptitude tests involving simulator driving, vision tests, and on-road driving assessment, a discussion session and, for drivers over 75, a cognitive screening test.

While clever folk worry about a possible test that would do the trick, three avenues offer a nearer-term prospect of working.

First, the wealth of driver-assist technology making its way into the modern motor car can help with everything from the mundane business of parking (a struggle when twisting and turning the body gets harder) to systems that detect other road users and on to the automatic application of the brakes. For these systems to be of most help, auto companies need to be encouraged to make them as intuitive as possible (have you read the owner's manual for your car? I thought not).

Second, we need to do more to assist older drivers in making informed decisions about their driving. Telematics could help – the infamous ‘black box' insurance policies that help make driving affordable for young people could generate information about driving style for older drivers too.

Regular check-ups with GPs and opticians – the RAC Foundation has long taken the view that eye tests should be compulsory for all drivers, repeated at least every 10 years with renewal of the photocard licence).

And third, perhaps all the effort that is going in to improve public transport options as a response to our climate change and air quality concerns will help create more comprehensive, more widely used services that, in turn, might help take some of the stigma out of hanging up the ignition keys.

For many relatively young people, ceasing to own a car is becoming something of a fashion statement, maybe it will become a badge of honour for older people too.