Tom van Vuren (pictured), a technical director for transport planning at Mott MacDonald, discusses climate change and transport modelling, and the need to rethink best practice

Many have commented on the impacts for transport planning of the Committee on Climate Change's (CCC) report Net Zero – the UK's contribution to stopping global warming. This is not surprising, given that transport is one of the chief contributors to greenhouse gas emissions – in the UK it accounts for more than a quarter of all emissions, mainly from cars and other light vehicles.

Transport planning has a role to play in reducing and removing emissions from the movement of people and goods, and the recommendations in the report's executive summary (a substantial 25 pages) illustrate this. These recommendations focus on four transport-related interventions:

- a shift to more active modes of travel

- transition to electric cars and vans

- development of hydrogen-fuelled HGVs

- recognition of the carbon-intensity and need for action on aviation and shipping.

Prime minister Theresa May has since sought to enshrine in law a commitment to reach net zero carbon emissions by 2050.

To me, it is inevitable that at least some kind, and also a significant amount, of transport modelling will be involved in identifying, which physical and policy interventions will contribute most and fastest to these issues.

A new approach to best practice

Time is of the essence and not everybody is on board. Having said that, for such modelling to be a useful tool in the quest for net zero, we need to consider some quite fundamental adjustments to current best practice.

Transport models tend to be estimated on currently displayed travel behaviour, observed now or in the recent past. These preferences displayed by current travellers are kept constant into the future. People respond to new alternatives (a cycle superhighway?), or changed conditions (increased congestion?), but their preferences as displayed in their observed behaviour remain essentially the same as now.

If the success of a net-zero policy relies on people adopting new, low-carbon behaviours, such models will underplay the effectiveness of new modes and green initiatives, ie: ‘If you keep doing what you've always done, you keep getting what you've always got.'

This is, of course, a big ask. Calibrating models using observed choices is a fundamental scientific aspect of transport modelling. We introduce objectivity and transparency, but the (implicit) assumption is that today's behaviours remain fixed in the future. Of course, recent academic research1 [see footnote] already questions such stability in, for example, driver licence holding among younger people, and the differential change in travel by men and women.

Did you know that between 2002 and 2017 the amount of road miles travelled by women stayed roughly constant, but men travelled 14% less? Modellers are trying to incorporate such observed changes into their forecasts; but for a net-zero future we need to also allow for currently unobserved changes in preferences, without losing the transparency and objectivity the fixed behaviour assumption has afforded us. What if the currently, mainly academic, #flyingless initiative really takes off across the population?

We also need to incorporate much better active modes, such as walking and cycling, in the strategic models usually built and used to support business cases for transport investment and policy development. The necessary spatial granularity for these modes, particularly walking, means that they are often hidden in network models, and even if they appear they are simplified into generated or abstracted demand from mechanised modes.

As a result, the potential to transfer current motorised trips into future walking or cycling trips is not well represented and not easily visible. Given the increasing interest in transport and health, and the wider benefits of active transport options related, for instance to place-making and gender inclusivity, such improvements to transport modelling would tick a number of other boxes too. Car ownership is generally modelled, but not the choice of vehicle type and fuel. It's not impossible: I came across an interesting academic article on a car technology choice model by Brand, Cluzel and Anable2 [see footnote].

Research and evidence on the take-up of low-carbon behaviours would need to feed into the specification and estimation of such models of future vehicle choice, and practical models need extending so this choice is fully reflected in transport planning.

The expectation in the CCC report of the costs of travel being lower for electric vehicles immediately raises the red flag of induced demand and here also models can inform the debate. The assumptions about future costs of car travel (electric, connected, autonomous, shared) are crucial and the literature abounds with often-conflicting numbers, but models can provide insights into the envelope of possible and plausible futures.

New ownership and use models also force us to address how travellers perceive the trade-off between up-front fixed costs and the day-to-day operational costs of cars – a currently under-researched and perhaps too simplified aspect of modelled travel behaviour.

Finally, the modelling of freight and logistics is generally limited to the observation of LGVs and HGVs as part of traditional traffic counts, and the application of growth factors – from national sources or higher-tier models – to the future. A fundamental shift in the propulsion of HGVs, from traditional internal combustion to hydrogen, may have wider-ranging implications for practical decisions by operators in the freight market – for example, the location of distribution facilities and the size of vehicles. Will this at last be the catalyst for developing freight models and best practice guidance that reflect the complexities of real-life logistics?

From land, to air and sea

Considering the size of the problem, the need for modelling in aviation and shipping (not my area of expertise) is not very much different from that for land-based transport. The Department for Transport's (DfT) consultation document Aviation 2050 – The future of UK Aviation estimates a growth of throughput in terminal passengers at UK airports of more than 50% between 2017 and 2050. And the UK Port Freight Traffic 2019 Forecasts, another recent DfT publication, estimates that by 2050 the tonnage shipped through UK ports will be almost 40% higher than now.

Again, this projected data does not differ greatly to the suggested increases in road traffic: 17%-51% anticipated growth between 2015 and 2050, according to the DfT's ‘Road Traffic Forecasts 2018' report. The real modelling challenge in aviation and shipping is that much of the forecasting is still rooted in ‘Predict and Provide'-style thinking, and I have seen little work on models that can help estimate and provide advice on how to reduce this demand. Technology is currently the only answer in consideration.

As a transport planner myself, I think the report misses some further considerations that would affect the country's ability to reach net zero, and where modelling can play a role in clarifying the options and implications. In particular, the opportunity that the integration of land use and transport planning offers to reduce the need to travel physically.

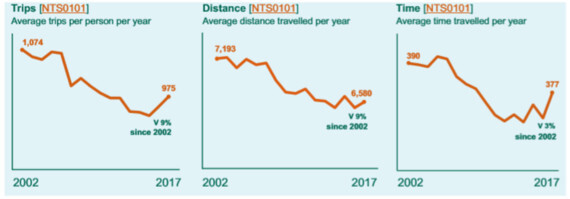

We have already seen, as illustrated in the results of the National Travel Survey, that the number of trips, the amount of time and the overall distance travelled has dropped in the past 10-15 years. Rather than electrifying the car fleet, planning cities and lifestyles that require less physical and certainly less motorised travel should be considered as part of the actions towards net zero. And we have models, such as land-use transport interaction models, that can calculate this.

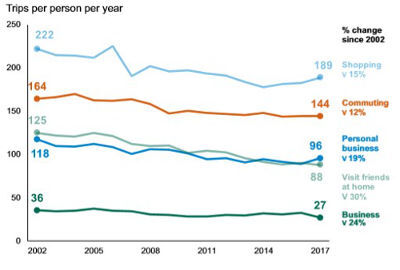

In the quest for net zero, academic research and transport modelling practice need to get together. Much of the progress in the former has not yet filtered down into the latter. Another challenge is how to better detect and reflect external influences on travel demand. Who had foreseen the impact of internet shopping and social media on trip-making (see charts above) – a drop in shopping trips of 15%, and for visiting friends and family, a drop of 30% since 2002.

Setting an example in the UK

At least, in the UK, most decisions related to transport investment and policy are underpinned by transport modelling: by agreeing assumptions and uncertainties; by understanding the strengths and limitations of the model approaches technically; by testing scenarios that reflect technological, political, environmental and economic uncertainty.

In this situation, I think the case is even stronger than usual. Transport models must provide inputs to public engagement – in what will inevitably be a sensitive and controversial debate on climate change – by testing what-if scenarios, explaining the effects of different timings and speeds of physical and transport policy measures to support transition to a net-zero future, illustrating the distributional impacts on different parts of society of doing nothing, and of doing alternative somethings.

1 Marsden, G. et al. (2018) All Change? The future of travel demand and the implications for policy and planning, First Report of the Commission on Travel Demand, ISBN: 978-1-899650-83-5).

2 https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0965856416302130.